November 4, 2016 – Christine Bordelon

Helping the recently incarcerated integrate more easily into society once they leave prison by giving them a place to live, a job and acceptance was the aim of the third annual Symposium for Systemic Change and Criminal Justice Reform held Oct. 21 at St. Agnes Parish in Jefferson.

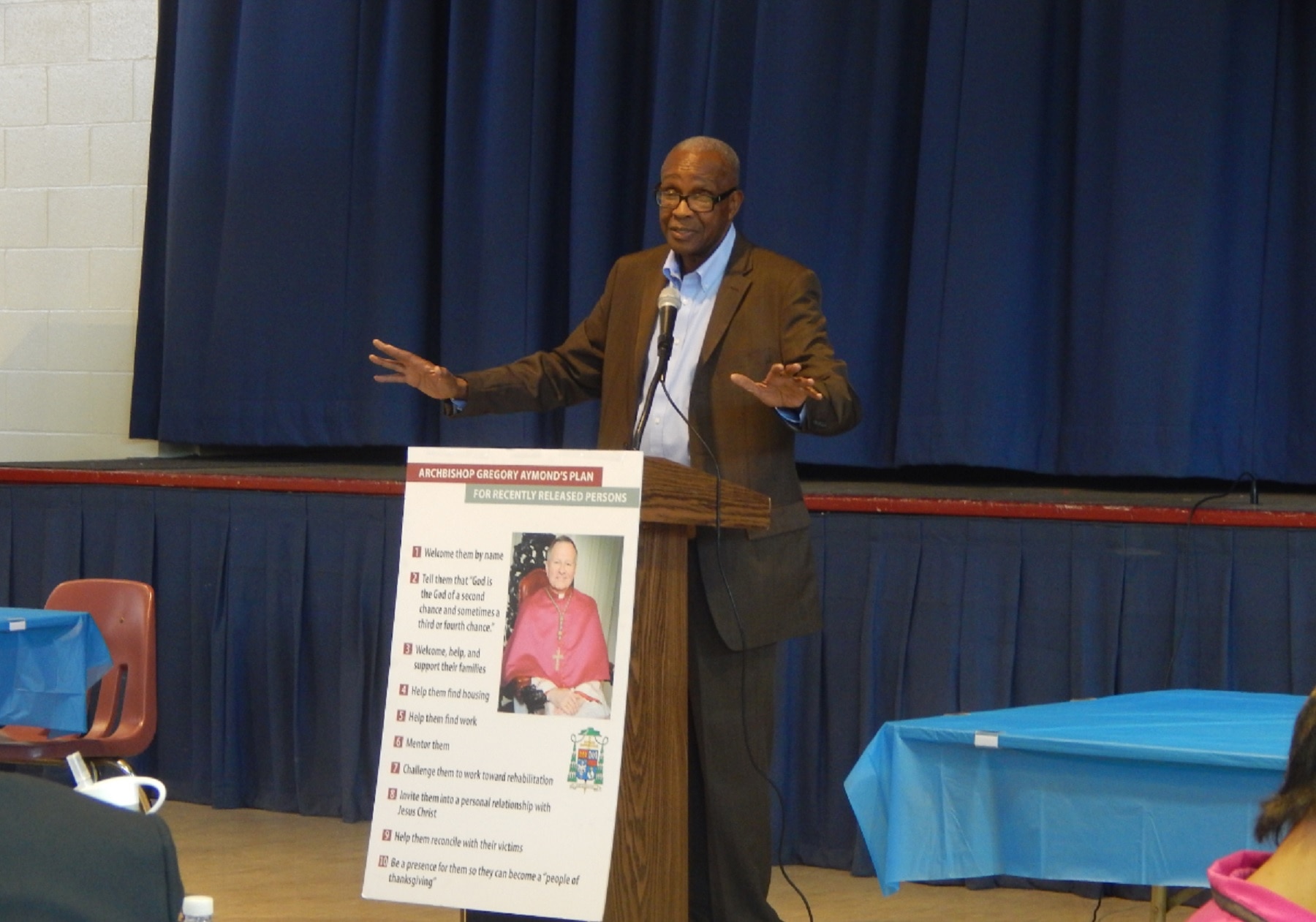

Archbishop Aymond addresses the attendees at the 2016 Symposium for Systemic Change and Criminal Justice Reform.

A Mass celebrated by Archbishop Gregory Aymond opened the meeting, followed by a Catholic panel with Archbishop Aymond, Eastern District U.S. Attorney Kenneth Polite, Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections assistant secretary Rhett Covington, Society of St. Vincent de Paul’s Deacon Rudy Rayfield and Catholic Charities’ Tom Costanza discussing “Advocating Justice and Ending Mass Incarceration.”

Archbishop Aymond said the job of Catholics is to truly welcome into their parishes those released from prison, emphasizing the critical nature of the first 72 hours after release.

“Jesus said, ‘When I was hungry, you gave me something to eat; when I was thirsty you gave me something to drink; when I was in prison, you visited me.’ I think today if Jesus were here, he would also say, ‘When I was released from prison, you welcomed me back into the family, the community of faith.’”

He suggested a 10-step process:

- Welcoming them back to the community and respectfully calling them by name;

- Demonstrating that God is a God of second chances by being the merciful face of forgiveness;

- Offering support to their families as they accept and walk with their formerly incarcerated family member outside of prison;

- Directing them to rehabilitation and a decent residence;

- Locating opportunities for work, education;

- Mentoring and accompanying them;

- Inviting them to a personal relationship with Christ by being an example of Christ, since research shows that faith helps by reinforcing morals;

- Helping them reconcile with their victims; how can that person make up for their mistakes, feel sorry and a sense of humility;

- Helping them become “a people of thanksgiving.”

“As you can see, this process demands a lot of responsibility and time, but it’s worth it because that person is a son or daughter of Christ and this could be a turning point in their life where they really can get their life back in order.”

Justice Dept. Initiatives

Polite, a St. Peter Claver parishioner, has been U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of Louisiana since 2013. Polite’s wide-ranged community outreach includes a 30-2+2 Reentry Collaborative that encourages companies to hire the formerly incarcerated for two years, and a student pledge against gun violence enacted in several schools. He mentioned how the state of California reduced juvenile school suspension rates by 89 percent and expulsion rates by 50 percent after eliminating subjective standards of discipline in the classroom.

Kenneth Polite speaks to the group about the effects of mass incarceration, specifically on children.

“When we talk at this conference about making systemic change, that’s what California did by making that one simple change, and juvenile crime rates continue to drop across the state. … There is much more to be done here. Our youth incarceration rate is six times that of England; 47 percent of youth released by juvenile custody are expected to return to custody within three years.”

He said young Louisianans deserve a second chance, and he is concerned about children of the incarcerated. When a parent of a child is in jail, that child is traumatized for life. Even before a parent goes to jail, that child could be exposed to drugs, drug deals, violence.

“What we are seeing on a day-to-day basis is young people who are children of the incarcerated experiencing significant levels of trauma in their lives,” Polite said. “The systemic change is this – make our systems trauma-informed. Our education, health and criminal justice systems must identify those individuals, as early as possible. … Individuals who experience that high rate of trauma ultimately will be the ones who have that high level of drug addiction (and) incarceration. Our responsibility is to stop it before it happens. Intervene as early as possible.”

Eliminate the Roadblocks

Covington, a parishioner of St. Alphonsus in Baton Rouge who works to expand re-entry opportunities for offenders, said the archbishop’s 10-point program is exactly what’s needed for the re-entry population. He stressed the importance of easing the formerly incarcerated back into society by eliminating impediments, getting them housing and jobs and removing the “offender” label.

“Mentoring is important,” Covington said, adding how a community benefits when it embraces the formerly incarcerated. “Even with the best program, if persons don’t have faith-filled relationships or positive social engagements, they are not going to be successful. You have to have the resources and accountability, but the public’s help is needed.”

Positive changes Covington has seen over the past few years include the opening of nine regional re-entry centers to bring the incarcerated closer to home, family and positive social connections.

“We have employed 20 transition specialists in the 26 largest jails in Louisiana to provide positive thinking for change, anger management, parenting, preparation to help them understand how to live differently,” he said. “We have long-term substance abuse treatment to address.”

The Legislature passed House Bill 802 to study criminal justice reform and better allocate resources for greater results.

Women Tell it Like It Is

A panel of women with the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls spoke of their struggles within and outside the prison system. They consider themselves the voice for those they left in prison.

The women’s panel shares their experiences with the group.

Syrita Steib-Martin with Operation Restoration said 56 women, including one of the speakers, were released from prison through President Obama’s 2014 clemency program that allows a petition with 100,000 signatures on a person’s behalf to be sent to the president’s desk for approval.

“There are a lot of women still in prison for violent and non-violent offenses and the only thing that will help them is us,” said Steib-Martin, who was incarcerated for 10 years. “They deserve a chance at mercy.”

Andrea James, former criminal defense attorney and founder of Families for Justice as Healing, said the council was started in a prison yard to give an accurate portrait of formerly incarcerated women. Women are the fastest-growing segment of the prison population.

“Many are suffering from the untreated trauma of sexual abuse and domestic violence,” James said. “The illness of addiction is never going to be cured in prison. Eighty-five percent of currently incarcerated women are mothers. In the federal prison system, we now have generations of women – the mother, daughter and grandmother. Their male counterparts also are in prison, many times on the same drug case. … Where does that leave our children? What kind of country takes all of the trusted adults away from children?”

She implored everyone to demand the release of women.

“We must not continue to be complicit, especially a people of faith, holding this unjust situation in place,” she said. “We have a responsibility to create change, because if you are complicit, you are just as guilty.”

Topeka Sam, who was in federal prison on a drug charge, said two Catholic women ministered to her in jail and helped her take responsibility for her actions, and she was able to forgive herself. She met others who created opportunities for her after her early release.

“It shows what God can do,” said Sam, who is pursuing a Christian ministry certificate.

Sam travels nationwide with the organization to raise awareness of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women and girls “to support each other and pass laws … with a goal to end incarceration of women and girls,” Sam said. “Women have no place in prison. When you put a woman in prison, you are destroying an entire community. … The children are left, and it becomes a cycle.”

What the Legislature Did

Rob Tasman, executive director of the Louisiana Conference of Catholic Bishops, gave a criminal justice reform update of the 2016 state legislative session. With a $2 billion deficit and a conservative-leaning Legislature, the session’s focus was economics, so the cost of incarceration was discussed. What passed: allowing a work certificate for previously incarcerated individuals that will encourage businesses to feel safe to employ them; “Ban the Box” legislation, meaning no longer would there be a checkbox on state civil service applications that asks if someone has a criminal record. (The Archdiocese of New Orleans does not include the checkbox on its applications but does do background checks.)

Lawmakers overwhelming passed a law to include 17-year-olds in the appropriate juvenile justice system, not an adult criminal system. They also established the Office of Juvenile Justice Schools governed by the state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, creating, for the first time a structure in the juvenile justice system for youth to continue school while incarcerated.

“Treating young individuals as young individuals as opposed to adults is critically important in terms of their rehabilitation, acknowledging their dignity,” Tasman said. The school assures that there is accountability in education and high expectations for youth to receive “something useful they can translate into skills” upon release.

In the 2017 legislative session, Tasman hopes to revive a failed bill that allows voting rights for individuals with felony convictions once released.

“This is currently a clear denial of a basic right of our citizens,” he said. “This is why we should all get engaged. I am here to encourage you that your voice matters. When legislators are flooded with emails, they take notice.”

Ronnie Moore shares his closing remarks.

Ronnie Moore gave closing remarks at the symposium. He is part of Catholic Charities’ Archdiocese of New Orleans and St. Vincent de Paul’s Cornerstone Re-Entry Project created in 2007 to rehabilitate the formerly incarcerated by teaching job ethics and skills for future employment. It has since expanded to address other re-entry concerns such as reuniting families of the formerly incarcerated and a mentoring program.

Listening, learning, discerning and designing new initiatives collaboratively to assist the recently incarcerated back into society was the symposium’s goal. Re-Entry 72 within the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office is one initiative in collaboration with companies to employ the formerly incarcerated. The Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office helps fund it.

Moore said individuals can participate in petitioning their legislators to change laws such as the right to vote and educating juvenile offenders. The next step, he said, will be participation in the Louisiana Re-Entry Advocacy Council as a vehicle for criminal justice reform.