by Peter Finney Jr.

It was Aug. 28, 1963, and Ronnie Moore, a freshly minted, 22-year-old civil rights activist from New Orleans, was sitting inside a Donaldsonville jail along with 300 others arrested for participating in a voting rights demonstration for African Americans in Plaquemine, near Baton Rouge.

Amazingly, the sheriff of the Ascension Parish jail had gone home to retrieve his black-and-white TV so the detainees could watch Dr. Martin Luther King deliver his clarion call challenging the conscience of a nation that for centuries had denied its black citizens full human rights.

On the fuzzy screen, the prisoners watched as King stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., and intoned: “I have a dream!”

Four days after the speech, Moore was out of jail, but for all anyone knew, he was as good as dead.

Moore had joined 200 other African American worshippers inside the Plymouth Rock Baptist Church in Plaquemine, pleading for the fulfillment of King’s long-delayed promise, an elusive vision that now looked so real they almost could pull it down from the heavens and touch it and kiss it.

Then, in the dark of night, came the tear gas, on orders from Louisiana Gov. Jimmie Davis.

So much for sunshine.

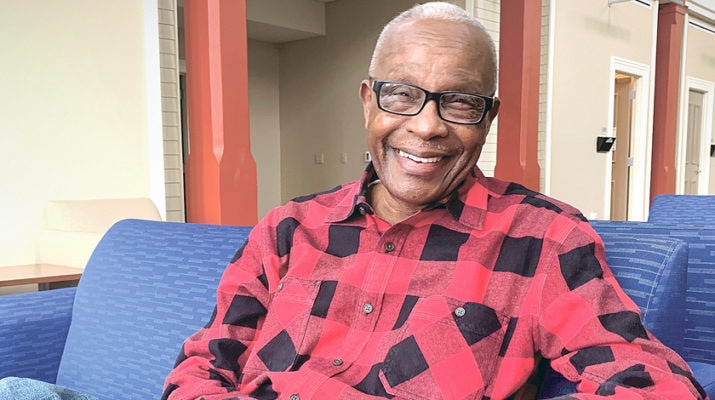

“I mean, they rode horses up through the church and into the pews,” Moore, now 78, recalled.

Davis felt it was important to break up the prayer rally, but police were especially looking for the youthful instigators like Moore. The police went door to door in the neighborhood, searching futilely until 3 a.m., but they didn’t realize that Moore and two other leaders had slipped through their cordon.

“The community folks put all three of us into a hearse and drove us out,” Moore said.

The curtains of the hearse, pulled tight, hid their bodies.

Two years earlier, at Southern University in Baton Rouge, where he became Student Council president, Moore had led 2,500 students on a seven-mile march from the campus to the state capitol in a demonstration for equal rights.

“It was a little more than going to a lunch counter,” Moore said, smiling. “It was like taking two thousand, five hundred students to the lunch counter.”

Because he operated the microphone and speaker system of the truck leading the march, Moore was charged with “illegal use of a sound truck” and jailed, along with 20 other students. The 21 Southern students spent 21 days, including Christmas, in the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison.

During his imprisonment, Moore caught a cold and started coughing up blood, which prompted one of his friends, Dave Dennis, to bang on the bars and complain.

“This man needs treatment now!” Dennis shouted.

“The guard grabbed Dave by the collar and took him to the hole,” Moore said. “So, I thought, oh my God, now what are we going to do? I told the guards, ‘I’m not eating this food until Dave is released,’ and all of us made that commitment not to eat. After a few days, they finally said, ‘If we send him back in here with you, there won’t be any banging on the door and y’all are going to eat.’ There had to be that control, of course. This was just the beginning of our whole journey.”

In the days before the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act, which gave blacks the legal right to vote, Moore’s most vital work as the field secretary of the Louisiana chapter of CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) was navigating the gauntlet of Jim Crow laws that obstructed black voter registration.

There were all kinds of byzantine roadblocks to black voter registration. One of the most creative obstacles, Moore said, was the birthdate trap: In order to register in Louisiana, you not only needed to know your date of birth but also had to calculate your exact age in years, months and days.

“The way we got around that is that on the day they went in to register, they gave us their birthdate information on the outside, and we told them what their years, months and days were, and they had to remember that,” Moore said.

Watershed moment

Moore concentrated his voter registration efforts on St. Francisville in West Feliciana Parish. He has committed one date to memory.

“That day – Oct. 17, 1963 – we had the first black registered to vote in St. Francisville,” he said. “The last one to attempt to register to vote, prior to that day, was in 1902, and he was lynched. Out of 42 who signed up on one day, three were able to register. But the miracle of the moment was there hadn’t been a black resident to vote in 60 years.”

None of this happened in a vacuum. A little more than a month earlier – on Sept. 15, 1963 – four girls were killed in a bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. On Nov. 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was gunned down in Dallas.

“I’m sitting in this restaurant in Plaquemine watching the news and Walter Cronkite comes on, crying,” Moore said. “We thought the end of the world was coming. We thought we would just lose it all.”

The hopeful signs of the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965 were followed by the assassinations of King and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968.

He was there

It’s no wonder when Moore visits high school classes today and talks about civil rights history, he often draws blank stares.

But, here’s the thing, he says.

“No one was prepared for King’s assassination or for Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, so even today, when people talk about whether or not progress has been made, I say, ‘You don’t know the depths of hell,’” Moore said. “So, I don’t even discuss that thing about ‘progress.’ What we learned from that experience is to understand that ‘This, too, shall pass.’ That is the guiding grace and focus of the type of struggle it will take to bring about change. We can never look back and never lose faith.”

Since 2007, Moore has given birth to Cornerstone Builders, a prisoner re-entry program of Catholic Charities Archdiocese of New Orleans that works one-on-one with male and female inmates, and their families, well before they are finished serving their prison terms.

Cornerstone Builders provides free bus transportation – 30 times a year – for relatives to visit families members while they are in prison. The organization is there as soon as the person walks out of the gates, providing a chance at housing, employment and re-entry skills. More than 400 persons have benefitted.

“You’ve got to have family or community contact when you’re coming out of prison,” Moore said. “That’s the biggest challenge we have. We need to mobilize all the church and faith-based groups to be a part of reaching these people in the present and meeting them at the gate when they come out.”

National award coming

He has successfully advocated for reducing the state’s prison population and using those savings for quality re-entry programs that reduce the recidivism rate. For his work, the Catholic Campaign for Human Development will honor Moore with the national Sister Margaret Caffery Development of People Award at a banquet in Washington, D.C., in January.

In September, he was inducted into the Louisiana State Prison Hall of Fame for his re-entry work. His next crucial goal is laying the groundwork for the state’s repeal of the death penalty, a proposal that last year made it out of committee for the first time in the state’s legislative history.

Moore recently went to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola and visited death row.

“While we were back there, I watched a guy explaining how a guy lays on the table and they do terrible things to a human being,” Moore said. “The journey now is to end the death penalty in Louisiana. I think I’ll retire when the Lord stops showing me things. But as long as I can see, I’m going to do.”

Conversion is possible

Moore believes in conversion. Imprisoned once in solitary confinement for his voting rights activities, he got out of jail only through a writ of habeas corpus signed by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black of Alabama.

“He was a member of the Ku Klux Klan, but he made it to the Supreme Court,” Moore said. “Therefore, I do believe in the conversions of people.”

Moore’s ex-offenders have tended gardens and worked in construction, rehabilitating themselves through what he calls “civic justice, which is rehabilitation through service and education.” They renovated the St. John’s Berchmans Manor of the Sisters of the Holy Family after Katrina.

“You talk about a miracle,” Moore said. “I told Sister Eva Regina Martin, ‘Sister, I don’t have nothing but formerly incarcerated people,’ and she said, ‘I don’t care – and I don’t have any money.’ We did it.”

His life has been a life of examination, a life lived for others. That life for others might best be summed up by his joyride – in a hearse.

“I think that the basic instructions before leaving this earth are faith, hope and love,” Moore said. “Those three virtues are also the gifts for changing the world. I’ve seen that at play over and over again. I’ve been speaking to dry bones all my days, and I keep seeing the resurrection. I just do whatever is revealed at that moment. I’m not asking God any questions.”